1

Introduction

1.1

This supervisory statement (SS) sets out the PRA’s expectations in respect of firms investing in illiquid, unrated assets within their matching adjustment (MA) portfolios. It is relevant to life insurance and reinsurance companies holding, or intending to hold, unrated assets (including restructured equity release mortgages (ERMs)) in an MA portfolio.

- 30/06/2024

1.2

This statement should be read in conjunction with regulations 4, 5, 6 and 7 of The Insurance and Reinsurance Undertakings (Prudential Requirements) Regulations 2023 (referred to here as the ‘IRPR regulations’), the Matching Adjustment Part of the PRA Rulebook and the Matching Adjustment Permissions statement of policy.1 In this statement, any reference to any provision of direct EU legislation is a reference to it as it forms part of assimilated law.

- 30/06/2024

1.3

To determine the basic fundamental spread (basic FS),2 the PRA expects that a firm will need to group the assets in an MA portfolio by credit quality step (CQS), asset class and duration. For assets with credit ratings provided by credit rating agencies3 (CRAs) and referred to in the Annex to Commission Implementing Regulation 2016/1800, the CQS and hence the assignation process for determining the basic FS, including any adjustments to reflect differences in credit quality by rating notch, is relatively prescriptive, with the only judgement being over the categorisation by asset class. In contrast, for internally-rated assets4, there is more judgement involved in determining the internal credit assessment and the CQS that should apply.

Footnotes

- 2. ‘Basic FS’ is defined in paragraph 5.7A of SS7/18 ‘Solvency II - Matching adjustment’, June 2024: www.bankofengland.co.uk/prudential-regulation/publication/2018/solvency-2-matching-adjustment-ss.

- 3. Credit rating and credit rating agency are defined in regulation 2(1) of the IRPR regulations.

- 4. For the purposes of this SS, an internally-rated asset is one where an internal credit assessment exists and is used for regulatory purposes. In relation to larger or more complex exposures, where an internal credit assessment exists alongside a credit rating from a CRA, firms are required to use the assessment that generates the higher capital requirement as per Matching Adjustment 7.4 and Article 4(5) of the Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2015/35.

- 30/06/2024

1.3A

Firms will also need to apply judgement in determining what fundamental spread (FS) additions5 (if any) should be made to the basic FS. Pursuant to Matching Adjustment 4.16 and 8.2, firms must apply FS additions for assets with highly predictable cash flows. Firms may also apply FS additions to any assets, not just assets with highly predictable cash flows, for example as part of the attestation process.6 The PRA expects a firm to pay particular regard to internally-rated assets when comparing its risk profile to the assumptions underlying the MA7 and considering whether FS additions may be needed.

Footnotes

- 5. Expectations regarding FS additions are covered in paragraphs 5.17 to 5.41 of SS7/18.

- 6. Matching Adjustment 4.17 and 9.1.

- 7. For the assumptions underlying the MA, see Chapter 1A of SS7/18.

- 30/06/2024

1.4

Firms need to have confidence that the risk management of these more complex credit exposures, in particular the internal credit assessment, CQS mapping and determination of the overall FS, is appropriate and in accordance with the assumptions underlying the MA. Firms also need to be satisfied that the size of the MA benefit claimed on them is fit for purpose, taking into account that MA contributes to firms’ capital resources. It is therefore expected that firms will be able to provide strong evidence to support the appropriateness of the steps taken to determine the MA, particularly for those internally-rated assets that present the greatest complexity and/or risk exposure.

- 30/06/2024

1.5

The PRA reminds firms of the responsibilities resting with Senior Management Functions in this context under the Senior Managers Regime (SMR). Specifically the:

- Chief Actuary is responsible for advising the board about the reliability and adequacy of the calculation of the technical provisions (TPs);8

- Chief Risk Officer is responsible for reporting to the board on the risk management strategies and processes in relation to credit assessments;9

- Head of Internal Audit is responsible for independent assurance on the adequacy and effectiveness of these processes and the firm’s accounting and reporting procedures;10 and

- Chief Financial Officer is responsible for the management of the financial resources of a firm and typically has the prescribed responsibility of the production and integrity of the firm’s financial information and its regulatory reporting (PR Q) and hence attestation of the FS and the MA.11

Footnotes

- 8. 7.1 of the Insurance – Senior Management Functions Part of the PRA Rulebook and 6 of the Conditions Governing Business Part of the PRA Rulebook.

- 9. Insurance – Senior Management Functions 3.3 and Conditions Governing Business 3.

- 10. Insurance – Senior Management Functions 3.4 and Conditions Governing Business 5.

- 11. 3.1(4) of the Insurance – Allocation of Responsibilities Part of the PRA Rulebook and Insurance – Senior Management Functions 3.2.

- 30/06/2024

1.6

Where material reliance is being placed on internal credit assessments and the CQS mapping for internally-rated assets, the Chief Actuary, Chief Risk Officer and, for the purpose of paragraph 1.5 above, the Chief Financial Officer will need to be satisfied that an appropriate FS is being applied, whilst the Internal Audit function will need to be satisfied that appropriate processes and procedures have been followed.

- 30/06/2024

1.7

Chapter 2 of this SS clarifies the PRA’s expectations where internal credit assessments are used as part of determining the basic FS, including some expectations that are specific to restructured assets (including ERMs). Chapter 3 then sets out some principles to be applied when assessing the risks from guarantees embedded within ERMs, for the purposes of verifying the appropriateness of the FS (including any FS additions); these apply to both restructured ERM notes and un-restructured ERMs that may be included in the MA portfolio under the limited proportion of assets with highly predictable cash flows. Chapter 4 sets out the PRA’s expectations regarding the risk identification exercise and the risk calibration and validation of internal models for illiquid assets.

- 30/06/2024

2

Use of internal credit assessments for assigning fundamental spreads

Expectations in relation to internal credit assessments

2.1

[First sentence moved to 2.4B] Matching Adjustment 7.2(1) states that internal credit assessments must have considered all possible sources of credit risk relevant to the exposure. This is particularly important when internal credit assessments are used as part of the process to determine the FS, because the FS should reflect the risks retained by the firm as per regulation 5(4) of the IRPR regulations.

- 30/06/2024

2.2

[Deleted]

- 30/06/2024

2.3

The overarching aim of the FS is to determine how much of the spread on an eligible asset should be taken to reflect the risks retained by the firm on the assumption that the asset is held until maturity (other than where it proves necessary to sell it, as part of rebalancing the MA portfolio, for the purpose of restoring the overall matching position where the asset and/or liability cash flows of the portfolio have materially changed). Retained risks include both qualitative and quantitative risks. Qualitative risks may include the strength of the terms and conditions in the loan agreement or a lack of default data. Quantitative risks may include economic or market stresses. Internal credit assessments must also consider how these risks may interact (as per Matching Adjustment 7.2(1)). The examples of risks listed in this paragraph are not exhaustive.

- 30/06/2024

2.3A

Regulation 4(4) of the IRPR regulations states that the credit quality of all MA portfolio assets must be capable of being assessed through either a credit rating or the firm’s internal credit assessment of a comparable standard. For assets with highly predictable cash flows this will provide some assurance on the appropriateness of the features and structure of the assets for backing liabilities in firms’ MA portfolios.

- 30/06/2024

2.4

[First sentence moved to 2.4B] As part of demonstrating that internal credit assessments are of a comparable standard to a credit rating as per Matching Adjustment 7.1(1), Matching Adjustment 7.2(2) requires that internal credit assessment outcomes lie within the plausible range of issue ratings that could have resulted from a CRA. Matching Adjustment 7.2(3) also requires broad consistency and no bias within the plausible range between firms’ internal credit assessment outcomes and CRA issue ratings at an asset type and the portfolio level. These requirements will help to give the PRA some assurance that the basic FS is appropriate. Having sample assets assessed by a CRA will additionally help demonstrate broad consistency between a firm’s internal credit assessment outcomes and comparable CRA issue ratings. Nevertheless, firms should not solely or mechanistically rely on credit ratings for assessing the creditworthiness of an entity or financial instrument.12

Footnotes

- 12. Article 5a(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1060/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council: www.legislation.gov.uk/eur/2009/1060/article/5a.

- 30/06/2024

2.4A

- 30/06/2024

2.4B

An internal credit assessment outcome will need to be mapped onto a CQS. Firms are reminded that performing an internal credit assessment and mapping an asset onto a CQS are two distinct processes. The PRA notes that the mappings of CRA credit ratings to CQSs are set out in the Annexes to Commission Implementing Regulations 2016/1799 and 2016/1800. For each internally rated asset type, a firm should consider how it has met the credit rating comparability requirements referred to in paragraph 2.4 above, when selecting appropriate CQS mapping scales from those applicable to different CRAs.

- 30/06/2024

2.5

Once a CQS and asset class have been assigned, firms are required to use the corresponding basic FS set out in the technical information published by the PRA as a starting point for the calculation of the MA (see the definition of matching adjustment in the Glossary Part of the PRA Rulebook, and Chapter 4 generally of the Matching Adjustment Part). Firms should not alter the CQS mapping of an asset on the grounds that they disagree with the technical information published by the PRA, eg if a firm’s opinion on the appropriate recovery rate for that asset differs from that specified in regulation 6(6)(a) of the IRPR regulations.

- 30/06/2024

2.5A

Firms must then further adjust the basic FS to allow for differences in credit quality by rating notch for the purposes of calculating the MA as per Chapter 6 of the Matching Adjustment Part. The PRA expects firms to consider their internal credit assessment outcomes by rating notch when determining whether they meet the ‘broad consistency and no bias’ requirement, and when assessing whether their internal credit assessment would exceed any rating caps from CRAs in meeting the ‘plausible range’ requirement (see paragraph 2.7B below for further detail).

- 30/06/2024

2.5B

The PRA also requires firms to validate their internal credit assessment processes used for assets within the MA portfolio as per Matching Adjustment 7.2(4) and obtain proportionate independent external assurance on the internal credit assessment outcomes as per Matching Adjustment 7.2(5).

- 30/06/2024

2.6

The PRA expects proportionate independent external assurance on a firm’s internal credit assessment outcomes to focus on the exposures that, in the firm’s view, present the greatest risk and potential for an inappropriately large MA benefit. In assessing the risk of an exposure to a particular asset type, the PRA expects firms to consider both the proportion and the absolute amount of the spread that is being claimed as MA, as well as the materiality of the exposure. Specifically, the PRA expects firms to focus on assets that present some or all of the following features:

- they are more complex (eg because they have been restructured);

- the absolute amount of MA benefit derived from the asset is material to the firm; or

- the MA benefit (expressed as a proportion of the total spread on the asset) is high either in its own right or when compared to the benefit from a comparable reference instrument.

- 30/06/2024

2.7

The PRA will calibrate thresholds around these features using data on firms’ asset exposures. For assets that exceed these thresholds, the PRA may request a firm to provide the results of any independent external assurance on its internal credit assessment outcomes, and seek further assurance where appropriate.

- 30/06/2024

2.7A

The PRA expects firms to develop a validation framework, including validation frequencies, coverage sample size, and risk tolerance thresholds for the credit rating comparability requirements that are referred to in paragraph 2.4 above. A firm should select the validation frequency and coverage sample size according to the complexity and materiality of its internally-rated assets. Firms should ensure that they have sufficient confidence that these requirements will still be met as market conditions change.

- 30/06/2024

2.7B

When establishing risk tolerance thresholds within the validation framework, for all assets, firms could determine the plausible range of issue ratings that could be achieved if the asset were rated by different CRAs (having regard to the requirements of Matching Adjustment 7.2(2)), taking into account any credit rating caps that may be applied by the CRAs. Risk tolerance thresholds for the ‘broad consistency and no bias’ requirement could be based on: (i) the proportions of the sampled assets that have higher versus lower notched internal credit assessment outcomes relative to the outcome of independent external assurance; (ii) the notch difference, across the sampled assets, between an appropriately weighted average internal credit assessment outcome compared to an appropriately weighted average outcome of independent external assurance; and/or (iii) any other reasonable methods that consider the distribution of notch differentials.

- 30/06/2024

2.7C

The PRA expects firms to resolve any validation failures that result in a lower basic FS being applied than is merited based on any internal validation and/or independent external assurance on the sampled assets. The PRA expects a firm to amend its internal credit assessment methodology, assumptions and/or processes, in order to resolve any validation failures. Where it takes time to eliminate such validation failures, a firm can apply an FS addition (as per Matching Adjustment 4.17) to compensate for the extent of any breaches of the plausible range, and any bias at an asset type or portfolio level, in order to ensure that the FS covers all risks retained by the firm.

- 30/06/2024

2.7D

If, as a result of either its internal validation or independent external assurance sought, a firm makes an adjustment to its internal credit assessment for one or more assets then the PRA expects any updated internal credit assessment outcomes to be used for the purposes of calculating the MA and any other relevant purposes, for example as an input to the Solvency Capital Requirement (SCR) calculation. Similarly, if a firm finds any potential weakness or issue with its internal credit assessment, and addresses it, but in such a way that it does not fully flow through to the MA calculation and/or any other relevant purposes, then the PRA expects the firm to take this into account when considering the appropriateness of its FS and MA as part of the attestation process and the adequacy of its SCR.

- 30/06/2024

2.8

[Deleted]

- 30/06/2024

2.8A

In order for a firm to evidence the robustness of its internal credit assessments, and hence provide assurance in respect of the assigned CQS and basic FS, the PRA expects the following areas to be implemented and documented.13 This is not an exhaustive list.

Footnotes

- 13. Conditions Governing Business 3.1(2)(b) and 3.1(2)(c)(iii).

- 30/06/2024

Identification of risks

2.8B

There should be an identification of all the risks affecting each asset and an assessment of how the firm has satisfied itself that it has considered all potential sources of systemic and idiosyncratic risk in its internal credit assessment. This should include consideration of the following factors at a minimum:

- external market factors;

- cash flow predictability;

- collateral;

- loan characteristics (eg refinancing risk);

- risks arising from third parties (eg sponsors, parties involved in the servicing and managing of the loan);

- legal, political and regulatory risks; and

- potential future risks eg impacts arising from climate change risks.

- 30/06/2024

2.8C

In addition, where a firm uses an internal model, the PRA expects the same underlying risk identification exercise to be used as a starting consideration for both the internal model and internal credit assessment process. However, a firm may justify why only a subset of the identified risks is then selected for inclusion in the internal model or credit assessment. This subset of risks may differ between the internal model and credit assessment.

- 30/06/2024

Internal credit assessment methodology and criteria

2.8D

The PRA expects firms’ internal credit assessment methodology and criteria to:

- set out the overall credit assessment philosophy and the ratings process;

- set out the scope of types of loans or entities to which the methodology applies;

- set out the scope of risks covered and define the credit and other relevant risks being measured;

- where a CRA has a published credit rating methodology for an asset type, have in scope at least the same range of risks, qualitative and quantitative factors and risk mitigating considerations, or justify any difference in the scope;

- describe how different loan features, risks, cash flow variability due to any non-default events and other relevant factors are assessed;

- set out the key assumptions and judgements underlying the assessment, including the treatment of assumed risk mitigating actions that rely on the firm’s own or outsourced processes involved in managing assets through their lifecycles;

- define whether the credit assessment is calibrated to a point-in-time or through-the-cycle;

- use both qualitative and quantitative factors; and

- explain the limitations of the internal credit assessment, for example, risks that are not covered, and when it would not be appropriate to allow for these limitations by overriding judgements.

- 30/06/2024

2.8E

The PRA expects a firm to justify its internal credit assessment methodology and to recognise any limitations.

- 30/06/2024

2.8F

Where a firm has decided that its internal credit assessment methodology for a particular asset type should be based on a CRA’s published credit rating methodology that is applicable for that asset type, the PRA also expects the firm to apply that methodology in full in the manner applied by the CRA.

- 30/06/2024

2.8G

Regardless of the choice of a firm’s internal credit assessment methodology, the firm should also describe how it has maintained broad consistency between its internal credit assessment outcomes and comparable issue ratings given by a CRA.

- 30/06/2024

Data

2.8H

The PRA expects firms to consider the availability, appropriateness, and quality of the data over the credit cycle on which their internal risk assessments and calibrations are based, and should clearly document how they have allowed for incomplete or missing data in the internal credit assessment. This includes consideration of whether the data is sufficient to support the proposed internal credit assessment and any adjustments to reflect differences in credit quality by rating notch.

- 30/06/2024

Expert judgements

2.8I

The PRA expects expert judgements made in the determination of the internal credit assessment to be transparent, justified and documented, and consideration to have been given to the circumstances in which judgements on the rating would be considered false. Furthermore, the history of judgements applied to deviate from the result of the internal credit rating methodology should be well documented, as should any other end-of-process overriding adjustments to the internal credit ratings themselves. The key judgements should be subject to the appropriate level of governance within the overall credit assessment process.

- 30/06/2024

Expertise and potential conflicts of interest

2.8J

The PRA expects to see evidence that the credit rating methodology and criteria development and approval, credit assessment and CQS mapping have been performed by individuals with relevant asset-specific credit risk expertise, competency and sufficient access to resources, who are independent and with minimised conflicts of interest. The PRA expects the individual with responsibility for the internal credit assessment function to be someone with appropriate experience and, where justified by the nature, scale and complexity of assets held by the firm, whose appointment to the role is approved by the management body and who has access to the management body on an ongoing basis. In particular, firms must ensure the independence of the internal credit assessment function and that effective controls are in place to manage any potential conflicts of interest as per Matching Adjustment 7.2(6), for example, between different stakeholders involved in the overall acquisition, origination and/or management of the assets.

- 30/06/2024

Validation

2.8K

The PRA expects that, as part of the requirement for a firm to have an internal credit assessment process that is subject to appropriate validation as per Matching Adjustment 7.2(4), the firm will have validated its internal credit assessment methodology and criteria, including how it has identified and allowed for all sources of credit risk, whether qualitatively or quantitatively. In addition, the PRA expects the firm’s validation to ensure that the internal credit assessment outcomes have satisfied the points in paragraph 2.4 above.

- 30/06/2024

Ongoing appropriateness

2.8L

The PRA expects that, as part of the requirement for a firm to have an internal credit assessment process that is subject to appropriate assessment of its ongoing appropriateness as per Matching Adjustment 7.2(4), the firm has satisfied itself that its internal credit assessments will remain appropriate over the lifetime of the assets and operate robustly under a range of different market conditions and operating experience. The credit assessments and CQS mappings should be reviewed by the firm at regular intervals, as well as in response to changes in relevant external market conditions or other factors that are expected to impact the rating. In addition to this, firms should monitor how the internal credit assessment criteria are applied consistently both within and across asset types.

- 30/06/2024

Process improvements

2.8M

The PRA expects firms to identify potential refinements needed to their methodology by monitoring their own credit experience against the internal credit rating assessments and changes made by CRAs to their methodology and criteria. This should include addressing any previously identified shortcomings in a firm’s internal credit assessment process (including any that were identified as part of the independent reviews mentioned in paragraph 2.5B above).

- 30/06/2024

2.8N

Where some or all of the internal credit assessment process is outsourced, the PRA expects firms also to demonstrate the effectiveness of the systems and processes that the outsourcer has in place, including validation, in order to ensure that outsourced internal credit assessments for assets satisfy the expectations set out in paragraphs 2.8A to 2.8M above and that the requirements of Article 274 of Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2015/35 are also satisfied. Firms should provide evidence that appropriate oversight systems and processes including governance are in place and have been carried out effectively for outsourced credit assessments.

- 30/06/2024

2.9

If the PRA judges that a firm is unable to provide satisfactory assurance using its own internal resources, it may choose to commission an independent review, which may take the form of a report commissioned from a skilled person under Section 166 of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (FSMA).

- 30/06/2024

Additional expectations in relation to internal credit assessments for restructured assets including equity release mortgages

2.10

The PRA expects that internal credit assessments for restructured assets will be anchored on a risk analysis of the legal documentation between all parties concerned. In the case of restructured ERMs, this includes, for example, the original loan agreement between the borrower and the lender, the contract between the originator and the insurance firm, and the legal structure of the notes issued by the special purpose vehicle (SPV).

- 30/06/2024

2.11

As mentioned in paragraphs 2.1 and 2.3 above, firms should consider both qualitative and quantitative sources of risk in their credit risk assessments. The PRA expects that all of the risks to which the senior notes are exposed (including combinations of risks) will be considered in the internal credit assessment, the assigned CQS and therefore the derivation of the basic FS (including any adjustments made to it in order to take account of differences in credit quality by rating notch).

- 30/06/2024

2.12

In respect of ERMs, some of the quantitative features the PRA would expect to be considered explicitly include (but are not limited to):

- underwriting terms of the underlying ERMs (eg prepayment terms, interest rate at which the loan will accrue, conditions attaching to the borrowers, conditions attaching to the property);

- exposures (eg loan to value ratios, ages of borrowers, health of borrowers);

- strength of security (eg location, state and concentration of the properties used as collateral, rights of the SPV to substitute underlying ERMs);

- leverage, including a full analysis of the cash flow waterfall between the loan receivables and the cash flows paid to the senior noteholder; and

- stress and scenario testing of the amount and timing of receivables, for instance as a result of:

- changes in the value of the properties that collateralise the ERMs, both in the immediate and longer term, including allowance for additional costs (eg dilapidation costs, transaction costs relating to sales);

- demographic risks relating to the borrowers under the ERMs (eg longevity trend and volatility, morbidity); and

- prepayment risk.

- 30/06/2024

2.13

Where these exposures involve a large number of homogeneous retail exposures, as would be expected in the case of most ERM securitisations, statistical approaches could be an acceptable proportionate method for assessing exposures and risks. However, the PRA notes this is unlikely to be acceptable for wholesale exposures (corporate lending and specialised lending) which tend to be large and heterogeneous.

- 30/06/2024

2.14

Where a firm has restructured an asset, eg an ERM portfolio, into a range of tranches, the spread on a given tranche should be commensurate with the level of risk to which that tranche is exposed. The more junior the tranche, the greater the spread would be expected to be in order to reflect the higher exposure to risk.

- 30/06/2024

2.15

Likewise the PRA would expect to see evidence that the securitisation structure provides loss absorbency to protect the senior note payments, eg a proportion of the cash flows accruing to the junior note in the early years of the transaction being kept in reserve in case of subsequent losses that reach the senior notes.

- 30/06/2024

2.16

Reliance on any credit-enhancing or liquidity-enhancing features should be carefully justified, taking into account the availability of these facilities over the expected lifetime of the SPV, including under stressed scenarios such as those referred to in paragraph 2.12 above.

- 30/06/2024

2.17

Qualitative factors that a firm may need to reflect in the internal credit assessment could include:

- uncertainty over the quantitative risk factors above resulting from a lack of data;

- the terms and conditions of the legal agreement(s) between the insurer and the SPV (eg cross-default provisions, covenants);

- uncertainty about the recoverability of the receivables when they become due (eg due to legal rights or practical considerations); and

- quality of loan servicing (eg ability to monitor properties and maintain knowledge of exposure and risk).

- 30/06/2024

3

Assessing the risks from equity release mortgages

3.1

This chapter sets out the PRA’s approach to assessing the risks to which insurers that invest in ERMs are, directly or indirectly, exposed. The assessment primarily covers the appropriateness of the amount of MA benefit arising from restructured ERM notes. The same principles apply in the exceptional case where a firm can justify including un-restructured ERMs in the MA portfolio under the limited proportion of assets with highly predictable cash flows, when assessing the appropriateness of the MA benefit (taking the FS addition in respect of these assets into account). In this case, the ‘Effective Value' of the un-restructured ERMs would simply be the sum of value of the un-restructured ERMs on the balance sheet and the MA benefit, and the economic value would be calculated based on the un-restructured ERMs in the same way as described in the rest of this chapter.

- 30/06/2024

Assessing the size of MA benefit from restructured ERM notes

3.1A

The size of the MA benefit arising from restructured ERM notes depends on the:

- contractually-agreed cash flows of the notes and the value placed on those notes, which will determine their spread; and

- FS assigned to the notes. The FS must reflect the risks that the firm retains in relation to the cash flows of the notes, including default and downgrade risk. These, in turn, will be driven by the risks presented by the underlying assets.

- 30/06/2024

3.2

ERMs are complex assets that often have embedded features such as a ‘no negative equity guarantee’ (NNEG) and no fixed maturity date. Restructuring them to produce MA-eligible notes with fixed cash flows adds a further layer of complexity. Also there are typically no CRA ratings or observable market prices for restructured notes on which firms and the PRA could place reliance.

- 30/06/2024

3.3

As with any securitisation, there is a risk that the valuation and/or credit assessment of the MA-eligible notes is not aligned with their true risk profile, leading to a spread that is too high or an FS that does not reflect all of the risks retained by the firm. As noted in paragraph 2.7 of this SS, the PRA will apply a higher supervisory intensity where it considers that there is a risk that the internal credit assessments on internally-rated assets, and hence the basic FS, may be inappropriate. The PRA also expect firms to pay particular regard to internally-rated assets when comparing their risk profile to the assumptions underlying the MA, when considering whether FS additions may be appropriate, as noted in paragraph 1.3A of this SS; this could also be subject to review by the PRA. For restructured ERM notes, this increased oversight will include both an assessment of the quality of the firm’s internal credit assessments (see paragraphs 2.10 to 2.17 of this SS), and a verification that the risks retained by the firm as a result of the embedded NNEGs have been appropriately allowed for, as described below.

- 30/06/2024

3.3A

Where a firm holds all of the tranches of a securitisation, the economic substance of its aggregate exposure remains the same regardless of the form of the securitisation. Understanding the risks posed to a firm by holding ERMs, in particular the NNEG, and how these risks have been distributed between the various tranches of restructured notes (for example in the FS of MA-eligible notes and the spread or valuation of the junior and senior notes), is an important part of ensuring that the MA does not arise from risks retained by the firm.

- 30/06/2024

3.3B

The approach to assessing NNEG risk set out under the heading ‘The Effective Value Test’ (the ‘EVT’) (below) is not the only method that could be used for these purposes, but it is consistent with principles (ii) to (iv) in paragraph 3.8 below and firms using this approach to demonstrate that they are not taking an inappropriately large MA benefit from restructured ERM cash flows will meet the PRA’s expectations for this assessment. Any alternative approaches that calculate property forward prices assuming property growth in excess of the risk-free rate while simultaneously discounting at the risk-free rate, without also making a sufficient allowance for the risk in the assumed property growth (as envisaged by principle (iv) in paragraph 3.8 below), are equivalent to assuming a negative deferment rate and would not meet principle (iii).

- 30/06/2024

Assessing the NNEG risk

3.4

The NNEG guarantees that the amount repayable by the borrower under the ERM need never exceed the market value of the property collateralising the loan at the repayment date. As such it is an important source of risk for an ERM. As part of the review of the amount of MA benefit being claimed by a firm, the PRA will assess the extent to which the contractual terms, value and rating of restructured notes properly reflect the underlying NNEG risks and the extent to which these underlying risks flow through to the notes held within the firm’s MA portfolio (and as such are effectively retained by the firm for these purposes).14 Compensation for these NNEG risks should not lead to an increase in the MA benefit. For example, assuming future house price growth in excess of risk-free rates should not lead to a lower valuation of the NNEG and hence higher MA, because firms are fully exposed to the risk that the excess house price growth will not be achieved.

Footnotes

- 14. The focus on the NNEG should not be taken to imply that other risks (eg prepayment risk) are not considered material by the PRA and indeed Chapter 2 of this SS is clear that these other risks should all be considered in the internal credit assessment.

- 30/06/2024

3.5

Assets such as ERMs generally do not have directly observable market prices, and so nor do they have directly observable spreads. Instead a spread must be derived, having first determined both a fair value for the ERM using alternative valuation methods as well as assumptions about cash flows.

- 30/06/2024

3.6

The presence of an NNEG will increase the derived spread on an ERM versus an equivalent loan without such a guarantee. It will also increase the amount of spread that should properly be attributed to risks retained by the firm.

- 30/06/2024

3.7

When determining the fair value of an asset for the purposes of deriving its spread, it is important that any embedded guarantees are valued consistently with the rest of the asset (ie on fair value principles).15 Otherwise, the component of the asset’s spread that is assumed to represent compensation for the risks arising from the guarantee may be underestimated. Further, it is not sufficient simply to ensure that the value placed on the asset as a whole represents a fair value, since there could still be an incorrect attribution of value between the NNEG and the other components driving the valuation.

Footnotes

- 15. The PRA’s rules on valuation are set out in 2.1 of the Valuation Part of the PRA Rulebook.

- 30/06/2024

3.8

The PRA will assess the allowance made for the NNEG risk against its view of the underlying risks retained by the firm. This assessment will include the following four principles, which are explained in more detail below:

- (i) securitisations where firms hold all tranches do not result in a reduction of risk to the firm;

- (ii) the economic value of ERM cash flows cannot be greater than either the value of an equivalent loan without an NNEG or the present value of deferred possession of the property providing collateral;

- (iii) the present value of deferred possession of property should be less than the value of immediate possession; and

- (iv) the compensation for the risks retained by a firm as a result of the NNEG must comprise more than the best estimate cost of the NNEG.

- 30/06/2024

3.9

[Deleted]

- 30/06/2024

(I) Securitisations where a firm holds all tranches do not result in a reduction of risk to the firm

3.10

Where a firm holds all of the tranches of a securitisation (as is generally the case for correctly restructured ERM portfolios), the economic substance of its aggregate exposure remains the same regardless of the form of the securitisation. Understanding the risks posed to a firm by the NNEG, and how these risks have been distributed between the various tranches of restructured notes, is an important part of ensuring that the FS appropriately reflects all of the NNEG risks that are retained by the firm in relation to the cash flows on the MA-eligible notes.

- 30/06/2024

3.11

Some of the exposure to the risks posed by the NNEG will remain in the junior tranches outside of the MA portfolio. Nevertheless it is important to verify that the combination of the spread on the junior tranche and the FS of the MA-eligible tranche(s) have appropriately covered all of the risks retained by a firm that holds the ERMs until maturity, including those that arise from the NNEG. For this reason the PRA will assess the overall ‘Effective Value’ of the restructured ERM against the components of the value of the un-restructured ERM (the ‘economic value decomposition’), as described below and illustrated in Figure 1 below.

- 30/06/2024

3.12

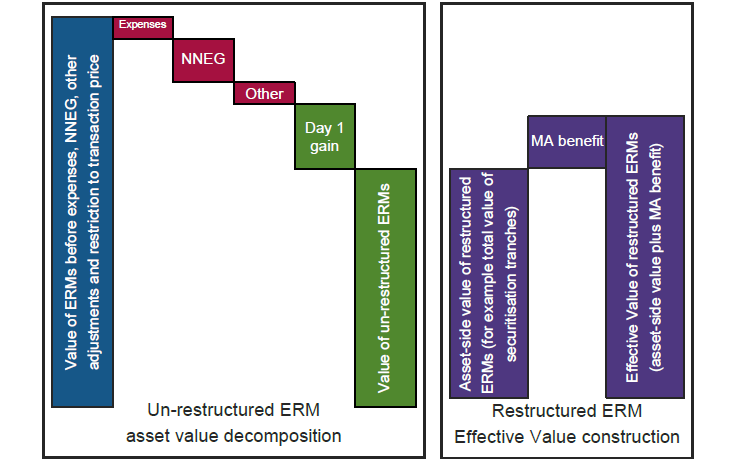

The ‘Effective Value’ of restructured ERMs is the total value of all tranches of the restructured ERMs on the asset side of the balance sheet, plus the MA benefit arising from the restructured ERMs on the liability side of the balance sheet. The right-hand side of Figure 1 illustrates the construction of Effective Value, alongside an illustration of one way in which the value of un-restructured ERMs can be made up. The total value of the securitisation tranches is illustrated as being somewhat lower than the value of the un-restructured ERMs, to reflect the frictional costs of restructuring, on the assumption that an equation of value holds.

- 30/06/2024

3.13

On the left-hand side of Figure 1, the value of un-restructured ERMs has been illustratively decomposed into:

- the value of expected ERM cash flows prior to deductions (ie as a risk-free loan on expected decrements) (in blue);

- expenses (in red);

- NNEG (in red);

- any other adjustments (for example to allow for pre-payment risk) (in red).

For the purposes of this SS, the remainder (in green) is referred to as the economic value of ERM cash flows. The PRA expects the Effective Value to be less than this amount.16 Calculation of the economic value should use methods and calibrations that are consistent with the other three principles.

Footnotes

- 16. The economic value has been broken down into the value of un-restructured ERMs and the restriction on the value to a transaction price, (labelled as ‘Day 1 gain’ in Figure 1 for brevity). The MA benefit has been illustrated in Figure 1 as partially offsetting the elimination of the Day 1 gain.

- 30/06/2024

3.13A

Where the SPV holds assets other than ERMs, the PRA expects firms to take the value of these other assets into account when conducting the EVT only if they are held for a purpose that supports the restructuring of the ERMs, for example to improve the credit quality of the restructured ERM notes, or to assist with risk or liquidity management, subject to the following expectations:

- (i) Other than as noted in (v) below, the balance sheet value of the other assets should be calculated in accordance with the PRA Rulebook and any other relevant requirements. This value of the other assets should be added to the economic value of ERMs.

- (ii) When determining Effective Value, firms should allow for the balance sheet value of the other assets in valuing each tranche. In particular, firms should allow for the impact on the security of the senior tranches arising from the other assets, and ensure that the valuation, spread and mapped CQS of the senior tranches reflects the presence of the other assets in the SPV, having regard to paragraph 2.4 of this SS. The PRA considers it would be difficult to demonstrate that the presence of a material value of other assets had no effect on the value or credit quality of the senior tranches and hence does not consider that it would be credible to assume that the value of the other assets was allocated in full to the junior tranche. The PRA expects a firm to be able to justify any allocation to the junior tranche in relation to the design of its restructuring approach.

- (iii) Firms should allow for any basis and counterparty risk associated with the other assets, for example any derivative or reinsurance contracts based on a property index are exposed to the basis risk of idiosyncratic property movements, as well as counterparty risk.

- (iv) Firms should allow for relevant costs associated with the other assets, for example commitment fees associated with liquidity facilities used to support the credit ratings of the MA-eligible notes.

- (v) For some assets other than ERMs, the PRA recognises that it may in principle be appropriate to depart from a balance sheet value calculated in accordance with the PRA Rulebook for the purposes of conducting the EVT. In particular, the PRA considers this may in principle be appropriate for some assets held to (partially) hedge NNEG risk. Where either a firm or the PRA believes it is appropriate to adopt a bespoke valuation approach for assets other than ERMs for the purposes of conducting the EVT, the PRA expects the firm to discuss and agree an appropriate valuation approach with its supervisor. In such cases, the PRA expects the firm to justify the relationship between the value of the asset for the purposes of the EVT and the allowance for NNEG risk included in the calculation of economic value.

The PRA expects firms to be able to demonstrate that the value of other assets has been allowed for in economic value and Effective Value in accordance with (i) – (v) above.

- 30/06/2024

3.14

The EVT assessment will be carried out on a firm-by-firm basis to provide assurance that all of the risks to which the firm is exposed have been appropriately reflected, either in the value of the securitised assets or in the FS assigned to those assets in the MA portfolio.

- 30/06/2024

Figure 1: Illustration of the construction of Effective Value

- 30/06/2024

(II) The economic value of ERM cash flows cannot be greater than either the value of an equivalent loan without an NNEG or the present value of deferred possession of the property providing collateral

3.15

This concept was introduced as the first proposition of paragraph 4.9 of discussion paper (DP) 1/16.17 It is derived from the following considerations:

- (i) Given the choice between an ERM and an equivalent loan without an NNEG, a market participant would choose the latter, since either the guarantee is not exercised, in which case the ERM and the loan have the same payoff, or it is, in which case the ERM pays less.

- (ii) Similarly, a market participant would prefer future possession of the property on exit to an ERM, given that the property will be of greater value than the ERM if the guarantee is not exercised, or the same value if it is.

Footnotes

- 17. ‘Equity release mortgages’ March 2016: see page 3 of 3 at www.bankofengland.co.uk/prudential-regulation/publication/2016/equity-release-mortgages.

- 30/06/2024

(III) The present value of deferred possession of a property should be less than the value of immediate possession

3.16

This statement is equivalent to the assertion that the deferment rate18 for a property is positive. The rationale can be seen by comparing the value of two contracts, one giving immediate possession of the property, the other giving possession (‘deferred possession’) whenever the exit occurs. The only difference between these contracts is the value of foregone rights (eg to income or use of the property) during the deferment period. This value should be positive for the residential properties used as collateral for ERMs.

Footnotes

- 18. By deferment rate, the PRA means a discount rate that applies to the spot price of an asset resulting in the deferment price. The deferment price is the price that would be agreed and settled today to take ownership of the asset at some point in the future; it differs from the forward price of an asset in that the forward price is also agreed today, but is settled in the future.

- 30/06/2024

3.17

It is important to note that views on future property growth play no role in preferring one contract over the other. Investors in both contracts will receive the benefit of future property growth (or suffer any property depreciation) because they will own the property at the end of the deferment period. Hence expectations of future property growth are irrelevant for this statement.

- 30/06/2024

(IV) The compensation for the risks retained by a firm as a result of the NNEG must comprise more than the best estimate cost of the NNEG

3.18

- 30/06/2024

3.19

[Deleted]

- 30/06/2024

The Effective Value Test (the ‘EVT’)

3.20

Firms can demonstrate that the Effective Value is less than the economic value of ERM cash flows (taking into account other assets held by the SPV in accordance with paragraph 3.13A above) using the following approach for calculating NNEG risk. Firms should calculate the allowance for NNEG risk for the portfolio of loans as the sum of a series of allowances for each ERM for each annual period during which ERM cash flows could mature, each allowance being multiplied by an exit probability appropriate to the annual period determined using best estimate assumptions for mortality, morbidity and pre-payment. Firms should calculate the allowance for each loan and period using the Black-Scholes option pricing formula shown below with the specified assumptions:

\[e^{-rT}\left [ KN\left ( -d_{2} \right ) -Se^{\left ( r-q \right )T}N\left ( -d_{1} \right )\right ]\]

\[\textrm{where}\: d_{1}= \frac{1}{\sigma \sqrt{T}}\ \left [ ln\left ( \frac{S}{K} \right ) +\left ( r-q+\frac{1}{2}\sigma ^{2}\right )T\right ] \textrm{and}\: d_{2}= d_{1}-\sigma \sqrt{T}\]

and N() is the standard Normal cumulative distribution function

- S = Current reasonable estimate at the balance sheet date of the value of the property providing collateral against the ERM;

- T = term to maturity as described above;

- K = loan principal and expected accrued interest at time T, calculated in accordance with the principles in paragraph 3.20A below;

- r = published Solvency II basic risk-free interest rate for maturity T, adjusted for use on a continuously-compounded basis;

- 𝜎 = published volatility parameter; and

- q = published deferment rate parameter

- 30/06/2024

3.20A

For ERM loans where the value of K at time T is dependent on borrower behaviour relating to principal or interest, the PRA expects firms to follow the principles below:

- (i) K should not include principal or the interest accruing thereon that is (a) projected to be lent after the date at which the EVT is conducted and (b) where the amount and timing of principal is at the borrower’s discretion or otherwise not known in advance by the lender.

- (ii) K should incorporate the principal and interest arising from a regular series of additional lending taking place after the date at which the EVT is conducted (a) where the amount and timing is known and certain in advance (other than any option to cease borrowing regular additional principal), and provided (b) that a best estimate of the rate at which borrowers cease to take additional borrowing is used.

- (iii) In the case of loans where borrowers pay some or all of the interest due as it accrues, K should reflect the expected accrual of interest at time T, allowing on a best estimate basis for the rate at which borrowers take up options to cease or reduce the interest they pay.

- (iv) Notwithstanding (i) above, the assessment of NNEG risk on existing lending should take account of any additional risk arising from future additional principal or interest arising from a pre-agreed lending facility, on a best estimate basis, having regard to the legal mechanisms by which future additional principal is expected to be incorporated into existing or additional restructured ERM notes. The purpose of this expectation is to reflect the risk to existing lending arising from future lending, and not the risks to which future lending would be exposed in itself. This is a potentially complex area and the PRA encourages firms to discuss their approach with their supervisor. In determining its best estimates of future lending, a firm should not take account of contractual variation terms that purport to allow the firm to curtail future lending in certain circumstances unless it can:

- a) justify that relying on such terms is consistent with its business plans with due consideration given to the franchise risk that could arise from such actions; and

- b) demonstrate it has considered carefully any legal and conduct requirements and expectations, including how a court might view these terms.

However, for the purposes of the EVT the PRA does not expect a firm to allow for risks to existing lending arising from future lending that is at the firm’s sole discretion (‘discretionary future advances’) and does not form part of a pre-agreed lending facility, subject to the firm demonstrating that this treatment of discretionary future advances for the purpose of the EVT has also had appropriate regard to relevant legal and conduct requirements and expectations.

- (v) Where the value of K is uncertain in a way not otherwise covered by the principles above, the PRA expects a firm to agree an appropriate approach to the calculation of K with its supervisor.

The PRA expects firms to be able to demonstrate that their calculation of K has been performed on a basis that is at least as prudent as that embodied in these principles. The PRA recognises that firms could adopt a range of methods that would meet these principles.

- 30/06/2024

3.21

The PRA expects firms to conduct the EVT with a minimum of the published value of q.

- 30/06/2024

3.21A

The values of q and 𝜎 will be published on the PRA’s website.19 The PRA expects to review the value of q twice a year and to publish an updated value, or to confirm the prior value, by the end of March and September each year. The PRA expects to review and update or confirm the volatility parameter once per year, by the end of September. The PRA may publish updated values more frequently and at other times of the year when it considers it is appropriate to do so, taking into account market conditions. When reviewing the values of q and 𝜎 the PRA will use the following framework:

- The PRA will use its judgement informed by a range of analysis to inform its decision on the values, rather than a purely mechanistic approach.

- For q, the PRA will have regard to movements in long-term real risk-free interest rates, measured using a range of swaps-based data sources, at a range of tenors from 10 to 30 years. In general, material increases in long-term real risk-free interest rates will lead to an increase in q, and conversely material reductions in long-term real risk-free interest rates will lead to a reduction in q, subject to the value of q remaining positive in line with principle (iii) of paragraph 3.8 above.

- For 𝜎, the PRA will update its analyses to take account of any additional data on property price returns and relevant advances in techniques for estimating volatility.

- To avoid spurious precision, in general the PRA does not expect to publish an updated value of q or 𝜎 that results in an absolute change of under 0.5 percentage points or 1.0 percentage points respectively.

- The PRA will set out a summary of its rationale for updating the parameters (or confirming their prior values) at the time of publication.

- The PRA will consult further in the event that it wishes to make substantive changes to this framework.

Footnotes

- 30/06/2024

3.22

Where firms are unable to meet the EVT using the above approach and cannot offer appropriate and credible explanations (or alternatives that are consistent with principles (ii) to (iv) of paragraph 3.8 above, as explained in paragraph 3.3B above) this will be an indication that they may be deriving an inappropriately large MA benefit from restructured ERMs. This could be because some or all of the contractual terms of the ERM re-structure, valuation and spread of the restructured ERM notes, the rating (and hence CQS mapping), and the FS of the restructured ERM notes, do not adequately reflect the risk profile of the ERM cash flows that underpin the restructure. In such circumstances, firms will need to consider whether to adjust one or more of those components in order to properly reflect that risk profile.

- 30/06/2024

3.23

Figure 1 shows an allowance for ‘other’ risks in the decomposition of economic value of ERM cash flows. The PRA will not assess each firm’s allowance for other risks using a single specified approach, because the size and nature of the allowance is likely to depend on the specific contractual terms and risk profile of each firm’s ERM cash flows. However, the PRA will expect firms to demonstrate that they have made a realistic and credible allowance for other risks when assessing the economic value of ERM cash flows. In particular, the PRA expects firms to include an allowance for the likelihood and potential impact of early pre-payment of ERMs, and a further allowance for the uncertainties discussed in paragraph 3.20A above.

- 30/06/2024

3.24

The PRA expects firms to conduct the EVT in the following circumstances:

- (i) when restructured ERM notes are established or amended;

- (ii) regularly in support of the Supervisory Review Process20: this should be at least annually at firms’ financial year end dates. For a firm where exposures to restructured ERMs (as a proportion of total assets in the MA portfolio) are more material, or if the PRA judges there to be an increased risk of the firm taking an inappropriately large MA benefit from restructured ERMs, the firm may be expected to assess more frequently, as agreed with supervisors;

- (iii) when recalculating the transitional measure on technical provisions, whether at a regular two-year recalculation point, or as a result of a relevant change in risk profile;

- (iv) where a firm has reason to believe that the result of the EVT would show that the test would no longer be met; and

- (v) on request by their supervisor.

Firms may wish to conduct the EVT for their own purposes at any time.

Footnotes

- 20. See ‘The PRA’s approach to insurance supervision’ available at www.bankofengland.co.uk/prudential-regulation/publication/pras-approach-to-supervision-of-the-banking-and-insurance-sectors.

- 30/06/2024

3.25

The PRA expects a firm to communicate the results and calculation of the EVT to its supervisor promptly, and as soon as possible in the event that the EVT result indicates that an inappropriately large amount of MA benefit may be derived from restructured ERMs. The results and calculation of the EVT should consist of a written statement setting out, for each separate securitisation, the following:

- (i) the effective date at which the test has been conducted;

- (ii) the value of q and 𝜎 used when conducting the test;

- (iii) economic value, as a total broken down into the major elements in Figure 1 above;

- (iv) Effective Value, as a total broken down into the fair value for each tranche of the restructuring, and the MA benefit arising from each eligible tranche; and

- (v) the result of the test (whether or not it has been met) together with any commentary that the firm considers to be relevant.

- 30/06/2024

3.25A

Where a firm chooses to use the EVT for attestation purposes, the PRA expects it to engage with the principles underlying the EVT and use its own assumptions that are judged to be appropriate when attesting that the MA can be earned with a high degree of confidence from the assets held in the relevant portfolio of assets (Matching Adjustment 9.1(1)(b)). These assumptions should not fall below the PRA’s published minimum parameters where applicable, with additional consideration given to any retained risks other than the NNEG that are not assessed by the EVT.

- 30/06/2024

Assessing the internal model SCR for restructured ERMs

3.26

The PRA reminds firms of the PRA’s expectations for modelling MA in stress in SS8/18 (Solvency II: Internal models – modelling of the matching adjustment) 21, in particular the expectations relating to using a different technique to the primary methodology when validating internal models for MA in paragraph 6.8 of SS8/18.

Footnotes

- 21. ‘Solvency II: Internal models – modelling of the matching adjustment’, June 2024: www.bankofengland.co.uk/prudential-regulation/publication/2018/solvency-2-internal-models-modelling-of-the-matching-adjustment-ss.

- 30/06/2024

3.27

The PRA considers that assessing the EVT in stressed scenarios could be a relevant validation technique in relation to paragraph 6.8 of SS8/18. Specifically, assessing the EVT in stress entails considering:

- (i) the stressed economic value of ERMs;

- (ii) the stressed value of other assets held by the SPV;

- (iii) the stressed Effective Value of restructured ERMs (derived from the stressed value and mapped CQS of the restructured ERM notes); and

- (iv) the relationship between stressed economic value and Effective Value.

The PRA considers reassessment of the EVT in stress, in particular the comparison of stressed economic value and Effective Value in (iv) above, to be a helpful validation exercise that could contribute to firms meeting the internal model requirements (see Chapter 14 of the Solvency Capital Requirement – Internal Models Part of the PRA Rulebook). When assessing internal model applications and firms’ continued compliance with the calibration standards22 and internal model requirements23 relevant for granting internal model permissions, the PRA will ask firms to apply a test based on the EVT in stress, to assist in providing assurance that the amount of MA in stress is not overstated. Firms may wish to consider adding an EVT in stress to their regular suite of validation tools.

Footnotes

- 22. See 3.3 and 3.4 of the Solvency Capital Requirement – General Provisions Part of the PRA Rulebook.

- 23. See Chapters 10 to 16 of Solvency Capital Requirement – Internal Models.

- 30/06/2024

3.28

Assessing the EVT in stress is not intended to replace firms’ existing primary approaches in their internal model methodologies for restructured ERMs. In particular, the PRA expects firms to follow the five-step framework set out in Chapter 3 of SS8/18, part of which entails re-valuing the MA portfolio assets and determining appropriate stressed FSs; this will require applying appropriate stresses to firms’ valuation methodologies and FS for restructured ERMs.

- 30/06/2024

3.29

Firms should apply a test based on the EVT in stress as a validation technique.

- 30/06/2024

3.30

Firms assessing the EVT in stressed scenarios should consider the following principles:

- (i) All the relevant inputs to the EVT should be stressed appropriately, including without limitation: the value of other assets; the opening property value, having regard to the risk that individual properties do not necessarily perform in line with a diversified index; the risk-free rate; mortality, morbidity and prepayment assumptions; best-estimate assumptions used in the calculation of the principal and interest; the deferment rate; and the volatility parameter. After allowing for appropriate diversification effects, the stresses should be consistent with the confidence level of 99.5% over a 1-year period for the SCR of the MA portfolio holding the restructured ERMs.

- (ii) The minimum deferment rate and volatility parameters for the EVT are set by the PRA using the framework in paragraph 3.21A above from time to time. These parameters are designed to inform a diagnostic test on the base balance sheet. The PRA expects firms to engage with the principles underlying the EVT and the framework for reviewing the parameters as set out earlier in this chapter, and to derive their own stresses to the deferment rate and volatility parameters. In doing so, firms may wish to consider adverse historical environments and prospective scenarios for property prices, both in the UK and internationally, as well as the framework for the parameters in paragraph 3.21A above.

- (iii) The deferment rate parameter of the EVT assessed on the base balance sheet has been set as a minimum view. Firms should therefore consider what the minimum view would be in stressed economic conditions, having regard to the levels of variables such as nominal and real interest rates, and property prices. A zero value for the deferment rate does not meet Principle III above, and so the PRA does not consider this to be a realistic or credible value when using the test to meet the intended purpose.

- (iv) Firms may wish to stress the inputs to the EVT in different ways depending on the design of their internal model. For example, firms could stress the risk-free rate r and the deferment rate q, or apply stresses to r and r-q. On the basis of the broad linkage between the deferment rate and real interest rates, firms may wish to consider changes in r-q as being broadly linked to implied inflation.

- (v) Firms should consider carefully the dependency structure among all risk drivers used in deriving stresses to the EVT parameters, in particular between r and q (or r and r-q), and ensure that the stressed scenarios used in the application of the EVT as a validation technique are economically realistic.

- (vi) Firms may wish to consider management actions to support the SPV under stress, for example injecting assets to support the credit quality of senior notes, or amending note cash flows. In respect of management actions, firms are reminded to consider carefully the relevant requirements as set out in Solvency Capital Requirement – Internal Models 11.8(3) and Article 236 of Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2015/35, and any implications for the MA eligibility of the restructured ERM notes or the MA portfolio as a whole.

- (vii) Firms should apply the EVT in a sufficiently wide range of scenarios to give reasonable assurance that the MA benefit in stress is not overstated. Where a firm’s internal model is based on Monte Carlo simulations, the firm could in principle limit the application of the EVT in stress to a key subset of the scenarios generated, provided they can demonstrate that the results of the test do not indicate that any material re-ranking of simulated scenarios would be required. The PRA considers that it would be good practice to apply the EVT in upside and downside scenarios.

- 30/06/2024

4

Risk identification and modelling of Income Producing Real Estate loans

4.1

This chapter sets out the PRA’s expectations of firms regarding the risk identification exercise and the risk calibration and validation of internal models (particularly in respect of the application of the MA within the calculation of the SCR) for illiquid assets. It includes, as an example, several expectations, specific to Income Producing Real Estate (IPRE) loans. Given the heterogeneity of illiquid assets, the PRA expects firms to consider whether these expectations are applicable to other relevant assets within their portfolios. Where firms consider the expectations are not applicable to assets with similar features to IPRE, the PRA expects them to provide, upon request, a justification of why this is the case. The PRA will seek assurance against these expectations in a proportionate way, using similar criteria to those discussed in paragraph 2.6 of this SS.

- 30/06/2024

4.2

IPRE lending refers to a category of funding to real estate where the prospects for ultimate repayment and recovery on the exposure depend primarily on the cash flows generated by the underlying property asset(s).24 The primary source of these cash flows would usually be lease or rental payments from commercial tenants (generally for the payment of interest and any amortizing principal) and the sale or refinancing of the asset(s) (generally for the payment of any non-amortizing principal at maturity). The distinguishing characteristic of IPRE (versus other corporate exposures that are collateralised by real estate) is the strong positive correlation between the prospects for repayment of the interest and principal due on the exposure and the prospects for recovery in the event of default. Both primarily depend on the realisation of cash flows generated by a property, whether these are in the form of rental income or sale/refinancing proceeds. Note that the PRA considers this definition to be a useful reference. However, it need not be applied rigidly and the PRA expects the expectations set out below to also be relevant for assets with similar features.

Footnotes

- 24. Basel Committee on Banking Supervision –The Basel Framework: IRB approach: overview and asset class definitions: www.bis.org/basel_framework/chapter/CRE/30.htm.

- 30/06/2024

4.3

The PRA’s observation is that IPRE loans are generally structured to isolate the collateral from the bankruptcy and insolvency risks of the other entities that participate in the transaction, eg via an SPV.

- 30/06/2024

4.4

The MA allows firms to adjust the relevant risk-free interest rate term structure for the purpose of calculating the best estimate of a portfolio of MA-eligible insurance or reinsurance obligations. To apply an MA, firms must have an MA permission from the PRA, as per Matching Adjustment 2.1. Firms with an MA permission are permitted to apply an MA for the purposes of determining both TPs and the SCR. The PRA expects firms to have confidence that the level of MA benefit assumed in each of these calculations is fit for purpose. The PRA’s expectations relating to modelling of the MA within the SCR calculation are set out in SS8/18. These expectations primarily apply to the risks arising in respect of corporate bond assets within firms’ MA portfolios. However, the PRA recognises that many of the expectations in SS8/18 would apply regardless of the assets held (see paragraph 1.8 of SS8/18).

- 30/06/2024

Risk identification

The role of the risk identification exercise

4.5

The PRA requires that ‘as regards investment risk, a firm must demonstrate that it complies with the Investments Part of the PRA Rulebook.’25 The Investments Part sets out the ‘prudent person principle’ which requires that firms ‘must only invest in assets and instruments the risks of which it can properly identify, measure, monitor, manage, control and report, and appropriately take into account in the assessment of its overall solvency needs in accordance with Conditions Governing Business 3.8(2)(a).’ Firms with an MA permission must also comply at all times with the prudent person principle requirements, as required by Matching Adjustment 2.2(6). See also the PRA’s expectations in SS1/20 (Solvency II – Prudent Person Principle).26

Footnotes

- 25. Conditions Governing Business 3.4.

- 26. ‘Solvency II: Prudent Person Principle’, June 2024: www.bankofengland.co.uk/prudential-regulation/publication/2020/solvency-ii-prudent-person-principle-ss.

- 30/06/2024

4.6

The PRA reminds firms that the SCR must capture all quantifiable risks to which firms are exposed27 whether using the standard formula or internal model, and internal models used to calculate the SCR must capture all material risks that firms are exposed to.28

Footnotes

- 27. Solvency Capital Requirement – General Provisions 3.3.

- 28. Solvency Capital Requirement – Internal Models 11.6.

- 30/06/2024

4.7

In order to ensure that these requirements are satisfied for IPRE loans, the PRA expects a firm to complete a comprehensive risk identification exercise that considers all sources of risks that the firm could be exposed to in relation to its IPRE loans. Due to the bespoke nature of IPRE loans, the risk identification exercise should consider features of individual loans. This applies to standard formula or internal model firms that have IPRE loans.

- 30/06/2024

4.8

The internal rating process (including internal rating models used to inform the FS and the MA benefit attributed to IPRE loans for the purposes of calculating TPs or for calculating the stressed FS) and the SCR should reflect the relevant risks identified in this risk identification exercise.

- 30/06/2024

4.9

The PRA expects a firm to be able to demonstrate that the IPRE loan risks captured by its internal ratings process offer sufficient discriminatory power in determining the credit quality of its assets and that these risks are reflected, as appropriate, in the internal rating models.

- 30/06/2024

4.10

The PRA expects internal model firms to use the risk identification exercise to influence the scope, methodology and calibration of the internal model used to calculate the SCR.

- 30/06/2024

4.11

Whilst the SCR may be calibrated to cover only a subset of the risks identified in the risk identification exercise, eg where some risks have been fully mitigated by a firm, firms are expected to clearly justify and explain any exclusions of risks identified in the risk identification exercise from the SCR calibration. Firms should also allow for any secondary risks introduced through risk mitigation.

- 30/06/2024

4.12

A firm using the standard formula is required as part of the Own Risk and Solvency Assessment to assess the significance of the extent to which its risk profile deviates from assumptions underlying the standard formula.29 The PRA expects the output of the risk identification exercise to be considered and incorporated into that assessment. In the event that the standard formula does not reflect the firm’s risk profile, the firm may need to consider whether it should use a partial internal model to calculate the SCR. For internal model firms, the internal model should be validated against the output of the risk identification exercise, noting any model limitations.

Footnotes

- 29. Conditions Governing Business 3.8(2)(c).

- 30/06/2024

4.13

The PRA expects the risk identification exercise to be carried out by persons with the appropriate skills and experience.

- 30/06/2024

4.14

The risk identification exercise should also take into account how the firm’s own or outsourced credit risk management processes may have an impact on the performance, and hence risks, of the assets.

- 30/06/2024

4.15

The PRA does not expect the risk identification exercise to be a one-off exercise. Firms are expected to undertake a risk identification exercise regularly to maintain an up-to-date view of existing exposures, and to capture potential risks arising from the known pipeline of new IPRE loans. Other circumstances that may require a risk identification review include, but are not limited to, changes to the risk appetite, changes in the legal, political or regulatory landscape, a significant change to external market conditions, a change in investment mandates, or the consideration of new IPRE loans.

- 30/06/2024

The process and scope of the risk identification exercise

4.16

In the risk identification exercise, the PRA expects firms to consider all relevant systemic and idiosyncratic risks associated with their IPRE loans.

- 30/06/2024

4.17

The risk identification exercise should consider features of existing individual IPRE loans and those that may be accepted in future in line with a firm’s risk appetite and tolerances set out in its underwriting policy and investment mandates. Grouping of assets by features may be acceptable but care is required to ensure no risks introduced by bespoke features are missed.

- 30/06/2024

4.18

The PRA also expects firms to consider interactions between the risks identified, and how any interdependence may affect both the outcome and impact of risks crystallising. For example, a reduction in the level of rent receivable from a commercial property would increase the probability of default through a reduction of the income coverage ratio, and increase the loss given default, through a reduction in the value of the property on which the loan is secured.

- 30/06/2024

4.19

The risk identification exercise should consider the following high-level areas, as a minimum:

- (i) external market factors, taking into account property market conditions (eg supply vs demand) and wider economic risks (eg interest rates, economic growth);

- (ii) cash flow predictability, taking into account for example the tenant(s), lease terms, voids and re-lettings;

- (iii) collateral, taking into account the characteristics (eg location, design and condition) of the underlying property(s), property and valuation risks, and ability to realise the collateral value within a timely manner and the security package;

- (iv) loan characteristics (eg leverage, serviceability, pre-payment risk, refinancing risk, covenants or structural protections);

- (v) risks arising from third parties, such as the strength of sponsor and its willingness to provide support, and parties involved in the servicing and managing of the loan, SPV and/or underlying property(s);

- (vi) concentration, basis and liquidity risks; and

- (vii) legal, political and regulatory risks.

- 30/06/2024

4.20

The PRA expects firms to demonstrate that they have appropriate skills and experience to implement the controls and risk management actions assumed in the management of IPRE loan exposures within the internal model. Firms should also demonstrate that these controls and risk management actions can be executed in the timescales assumed. Where this is not possible, firms should consider the extent of any differences between the assumed and actual effect of controls relating to the management of IPRE loan exposures, including timeliness and whether any adjustments are necessary to the internal model as a result.

- 30/06/2024

4.21

The PRA expects a firm’s risk identification exercise and the assumptions underpinning its internal model to reflect the risk profile of the firm’s IPRE loans. This will be influenced by relevant policies and practices of the firm relating to IPRE lending. Such policies and practices are likely to cover the following areas:

- (i) underwriting of loans, eg the criteria upon which the approval of any loan is based,30 and the impact this may have on the risks accepted on IPRE lending;

- (ii) the due diligence process applied to a loan, including any documented standards, relating to IPRE loans that may be applied to sponsors, borrowers, contracts, collateral property and security package;

- (iii) agreements between the firm and an internal or external IPRE loan investment manager relating to the obligations of the investment manager,31 eg investment mandates;

- (iv) legal protections required through loan covenants or structural protections;

- (v) potential conflicts of interest relating to IPRE lending, including identification and management thereof;32

- (vi) outsourcing of any functions relating to IPRE lending,33 where relevant;

- (vii) ongoing administration, servicing and monitoring of IPRE lending;34 and

- (viii) dealing with any distressed assets,35 eg through the workout process.

Footnotes

- 30. Article 261 (1)(a) of the Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2015/35.

- 31. Article 274 (3)(c) of the Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2015/35.

- 32. Article 258 (5) of the Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2015/35.

- 33. Article 274 (1) of the Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2015/35.

- 34. Article 261 (1)(c) of the Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2015/35.

- 35. Article 261 (1)(c) of the Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2015/35.

- 30/06/2024

Impact of loan underwriting practices on risk profile

4.22